Tech companies find themselves in an awkward position in the lead up to a recession, and you almost can’t run one without having some sort of macro view (whether self-aware or implicit). The reason for this has to do with why tech is an attractive sector in the first place.

The magic of a proper tech company is the ability to scale costs linearly while scaling revenues exponentially. While this does lead to capital shortfalls as the business ramps, once escape velocity is reached, the nonlinear relationship between costs and revenue makes them wildly profitable.

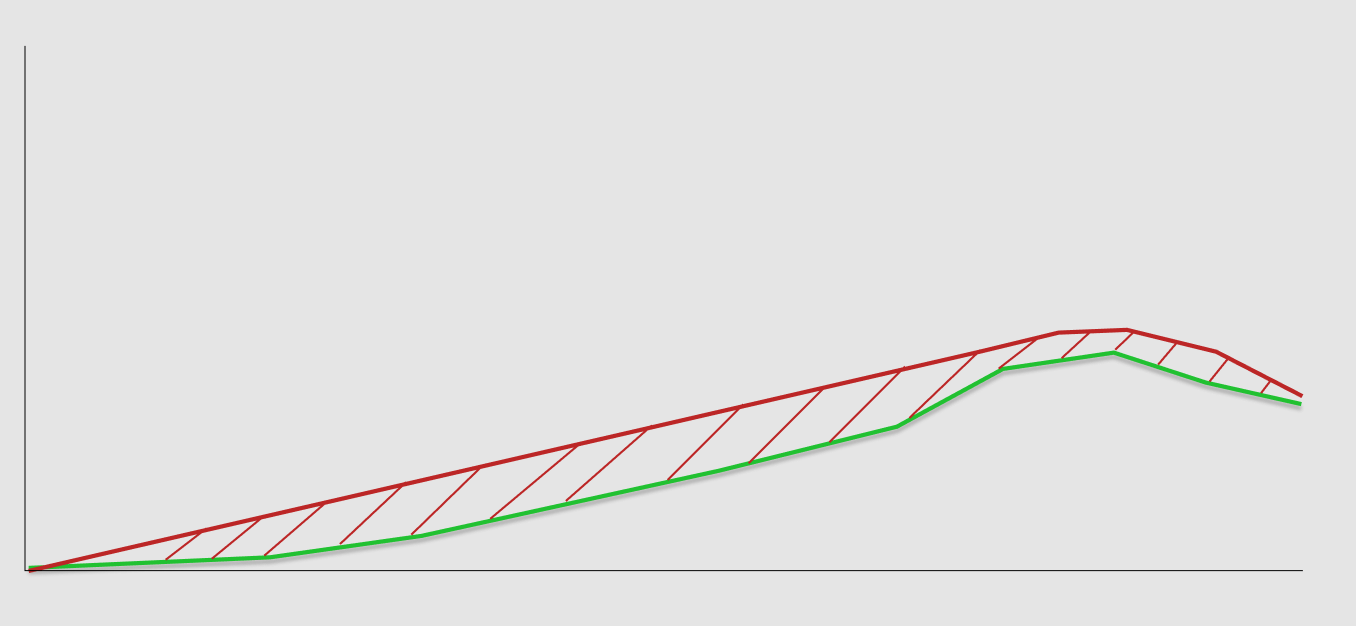

The amount of capital a business needs in order to become profitable is essentially the area defined here in the chart, before the exponential revenue function is attempting to catch up to the linear cost burn:

Okay so what happens when this sort of thing comes along? This is the incremental revenue for Datadog, and as you can see the rate of change has fallen off pretty hard here:

Well… now things get hard. We’re staring down the barrel of something like this, and we’re roughly at the labeled point — the second derivative is falling of pretty hard, and looking like it may even flatten out or decline. So now company leadership has to have a macro view, at least about whether we’re facing a proper recession, because the way they react here matters a lot.

Remember: the area in red is the amount of cash on hand needed for survival.

There are essentially two options here — be proactive, or be reactive to events as things continue to play out.

The trouble with responding to events in realtime is that it still significantly increases cash requirements, and can lead to a situation where instead of “paying for growth” the business is either 1) overpaying for growth, relative to the ‘value of growth,’ or 2) running in place while paying a growth-like premium for operations.

Companies in these situations can often find that funding dries up rather quickly, and precisely at the moment it’s needed the most. This is not a fundable shape:

This is in part why we often see tech companies start making cuts early on in a recession — if management believes there is a high probability that a recession is coming, being proactive is a way to ensure that the cash requirement area defined in the original plan stays static, and if executed swiftly can even lead to a modest cash buffer.

This sort of cash buffer is wildly useful: the company can use it to accelerate out of the other side of the recession, or to fund attractively priced acquisitions as we go through the worst of it.

When we see the tech industry start to cut costs en masse, this is what they’re doing — they’re taking in their sails to survive the storm.

And when we see players like Stripe (a company that has a lot of information about economic activity) move forward with large cost reductions as economic data weakens across the board, it’s a fairly interesting indicator that these operators believe we’re headed for turbulent waters.

They’re looking to avoid getting caught out, and to capitalize on what’s coming.

I have seen commentary suggesting that the ongoing tech layoffs could be ignored as the overall numbers of people involved are not a significant percentage of the labor force. This explains well why we should indeed be paying attention to tech as a useful leading indicator.

Stripe was indeed the strongest signal confirmation of what’s ahead. It is both a coincidental and a leading indicator.